Membership analysis of M37 Open Cluster- II DBSCAN

I continue with the membership analysis for the stars in the M37 cluster, testing various algorithms, adjusting parameters, and comparing the results with the available literature. In this post, I will focus on refining the analysis with DBSCAN and analysing its results.

This is a long post, which includes concepts about stellar evolution and the clusters themselves.

Membership analysis

Introduction

In the first part, I explained how to perform a basic analysis of membership in an open cluster based on data downloaded from Gaia for a given region. In the following entries in this series, we will perform a much more rigorous membership analysis, using several unsupervised classification algorithms (DBSCAN, HDBSCAN, and GMM), comparing the results with each other and with available publications. The three methods are widely used in various articles addressing the problem of membership in open clusters. Other articles also use other supervised classification algorithms such as K-means, but I decided to discard them for the time being, as they require already labelled data for model training. For now, I will perform an analysis with three dimensions available in Gaia: parallax and proper motions in right ascension and declination.

Looking through the literature, I find that M37 is a well-studied cluster, which allows me to compare the results obtained and validate my project.

As in previous articles, the data I will use is downloaded from Gaia DR3 (Gaia Collaboration, Vallenari, La., et al. (arXiv) (ADS)). The Gaia DR3 database is the third data release and provides some 1.81 billion objects, of which 1.47 billion have complete astrometry and photometry data. In particular, the extremely high-precision parallax and proper motion data will be used here for membership analysis.

The description of some of the Gaia data is important to highlight at some point in this series of articles, and probably deserves an article of its own.

According to the literature found or the SIMBAD page for M37 itself (https://simbad.cds.unistra.fr/simbad/sim-basic?Ident=ngc2099&submit=SIMBAD+search), the main data for the cluster are:

| RA (α) | Dec (δ) | pmra (μ_α) (mas/yr) | pmdec (μ_δ) (mas/yr) | parallax (π) (mas) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 88.074 | 32.545 | 1.924 ± 0.06 | -5.648 ± 0.05 | 0.666 ± 0.07 |

I will use this data to download and filter Gaia data and to compare the results obtained.

Downloading Gaia DR3 data

To download Gaia DR3 data, I follow the same method I used previously with the following parameters:

RA (α): 88.074Dec (δ): 32.545search_radius:1.5º

By choosing 1.5º, I aim to recover data not only from stars in the centre of the cluster, but also from stars in the nearby corona and even some of the stars that are evaporating. An even larger radius might be appropriate for a more comprehensive study that includes the tidal structures of the cluster. I will not do this at this time, but it is noted as a feature to consider for inclusion in later versions of the code.

Standard filters on the Gaia data are also included:

FROM gaiadr3.gaia_source

WHERE 1=CONTAINS(

POINT('ICRS', ra, dec),

CIRCLE('ICRS', {cluster_ra}, {cluster_dec}, {search_radius})

)

AND parallax IS NOT NULL

AND parallax/parallax_error > 5

AND pmra IS NOT NULL

AND pmdec IS NOT NULL

AND ruwe < 1.4

AND phot_g_mean_mag < 20

With this data, the Gaia query returns 53,109 stars, with the following basic statistics:

Number of stars: 53109Mean Parallax: 0.84 ± 0.88 masMean μ_α: 1.19 ± 5.32 mas/yrMean μ_δ: -4.55 ± 7.60 me las/yr

Filtering the downloaded data

The query returns more than 53,000 stars, a large number, and most of them probably do not belong to the cluster. Here I decided to apply a filter before applying the classification algorithms. It is quite clear that in this query there are many stars in the same field of view that do not belong to the cluster. Let us now consider that the cluster consists precisely of stars that were born in the same area and move in more or less the same way (with some dispersion, of course). To reduce subsequent processing and eliminate errors, I am going to filter the data based on existing knowledge about the M37 cluster: the parallax values and proper motions of the cluster members must be close to the already known value. We filter the data close to these known values and eliminate the rest, refining the process, reducing subsequent computational costs and reducing errors. How do we decide on the values to filter? I consider the following: when I decide on a range for filtering, I must take into account that the Total Dispersion of the members’ values will be composed of:

Total Dispersion = intrinsic dispersion + measurement errors

Intrinsic dispersion: not all stars in the cluster move at the same speed. There is a dispersion of velocities that may be due mainly to internal gravitational interactions between them, close encounters between two stars, binary stars that create movements as they orbit each other, or stars that escape from the cluster with anomalous velocities. These dispersions in velocities can be roughly estimated as:

- Young clusters (<100 Myr): σ_v ~ 0.5-1.5 km/s

- Intermediate Clusters (100-500 Myr): σ_v ~ 0.3-1.0 km/s

- Old clusters (>500 Myr): σ_v ~ 0.2-0.8 km/s

The estimated age of M37 is 500 Myr, and I will choose a somewhat wide range. If I include too many stars, I hope that the clustering algorithms will filter out the stars that do not belong. The range set in the filter is σ_v ~ 0.5–1.0 km/s, which can be translated to mas/yr using the formula:

μ [mas/yr] = (v_transversal [km/s] / d [pc]) × 211.09The estimated distance of M37 is 1500pc, so the range values would be:

σ_μ = (0.5 km/s / 1500 pc) × 211.09 = 0.070 mas/yr (mínimo) σ_μ = (1.0 km/s / 1500 pc) × 211.09 = 0.141 mas/yr (máximo)That is, it would add an intrinsic dispersion σ_μ ~0.07 - 0.14 mas/yr.

Gaia measurement error Gaia measurement errors are related to several factors: magnitude (fainter stars have greater error), regions of the sky with greater or lesser star density, number of observations… Typical errors by magnitude are:

G Magnitude Error Description G < 14 error_μ ~ 0.02-0.05 mas/yr brightest stars 14 < G < 16 error_μ ~ 0.05-0.15 mas/yr intermediate stars 16 < G < 18 error_μ ~ 0.15-0.50 mas/yr weak stars Once again, I will choose a wide range: σ_error ~ 0.10-0.25 mas/yr, taking into account that the stars that contribute most to the cluster are in the range G=12-17.

When combining errors:

σ_total = √(σ_intrinsec² + σ_error²)

so total expected dispersion is ~0.2 - 0.3 mas/yr

- Security margin

In practice, there are other causes that can affect the dispersion of the cluster. A robust rule of thumb is to use ±3σ to ±5σ around the expected value:

±3σ → captures 99.7% of a normal distribution

±4σ → captures 99.99%

±5σ → very conservative

I prefer to be conservative and use 5σ, which would give us a safety margin of σ_safety 1.25mas/yr for μ_α and μ_δ.

Overall, I settle on a range for proper motions of μ_α from 0.7 to 3.0mas/yr and μ_δ from -7.0 to -4.0

- Parallax limits To filter the parallax and stay within reasonable limits that include the stars in the cluster and minimise field stars, I take into account the values estimated in the literature. The estimated parallax of M37 is 0.666mas (distance ~1500pc). The typical dispersion of an open cluster is between 10-50pc, which at an approximate distance of 1500pc would correspond to a parallax margin of ±0.01-0.05 mas. We add a margin of error in the Gaia measurement (~0.05-0.10mas). So, to be conservative, in order not to exclude stars from the cluster in the filter, I set a parallax range of 0.50-0.85mas.

Applying these limits to the data downloaded from Gaia, I obtain:

- `Number of stars`: **3377**

- `Mean Parallax`: **0.67 ± 0.08 mas**

- `Mean μ_α`: **1.86 ± 0.45 mas/yr**

- `Mean μ_δ`: **-5.50 ± 0.62 mas/yr**

As a final step, I normalise the data to bring it all to a similar scale so that higher values in one of the parameters do not dominate the analysis.

Membership analysis with DBSCAN

DBSCAN (Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise) is an algorithm that clusters points based on their local density. The algorithm has two main parameters:

eps: the maximum distance between two points for them to be considered neighbours.min_samples: the minimum number of points required to form a dense cluster.

DBSCAN is particularly good for clusters because:

- It does not assume that clusters are spherical in shape.

- It can identify points as ‘noise’ (outliers)

- It does not need to know in advance how many clusters there are

The truth is that I have not yet found a method to decide what the optimal values are for each cluster, because they do affect the result of the algorithm, and they do not seem to behave the same in each cluster. In my case, after several tests, I have settled on these values:

eps: 0.3min_samples: 20

With this values I get the following results:

Number of clusters identified: 1Stars classified as noise (field): 1773Stars classified in main cluster1689Parallax: 0.67±0.05masμ_α: 1.88±0.15mas/yrμ_δ: -5.62±0.15mas/yr

These values are remarkably consistent with other studies and with SIMBAD’s own data. Thus, Cantat-Gaudin et al. (2018) obtain Parallax: 0.66mas, μ_α:1.92mas/yr and μ_δ: -5.64. M Noormohammadi, M Khakian Ghomi, A Javadi (2024) obtain Parallax: 0.67 ± 0.08mas, μ_α:1.87 ± 0.09mas/yr and μ_δ: −5.62 ± 0.06mas/yr using a combination of DBSCAN and GMM.

Analysis of results

I will now analyse the results obtained, which will allow me to learn in detail many of the physical concepts behind them.

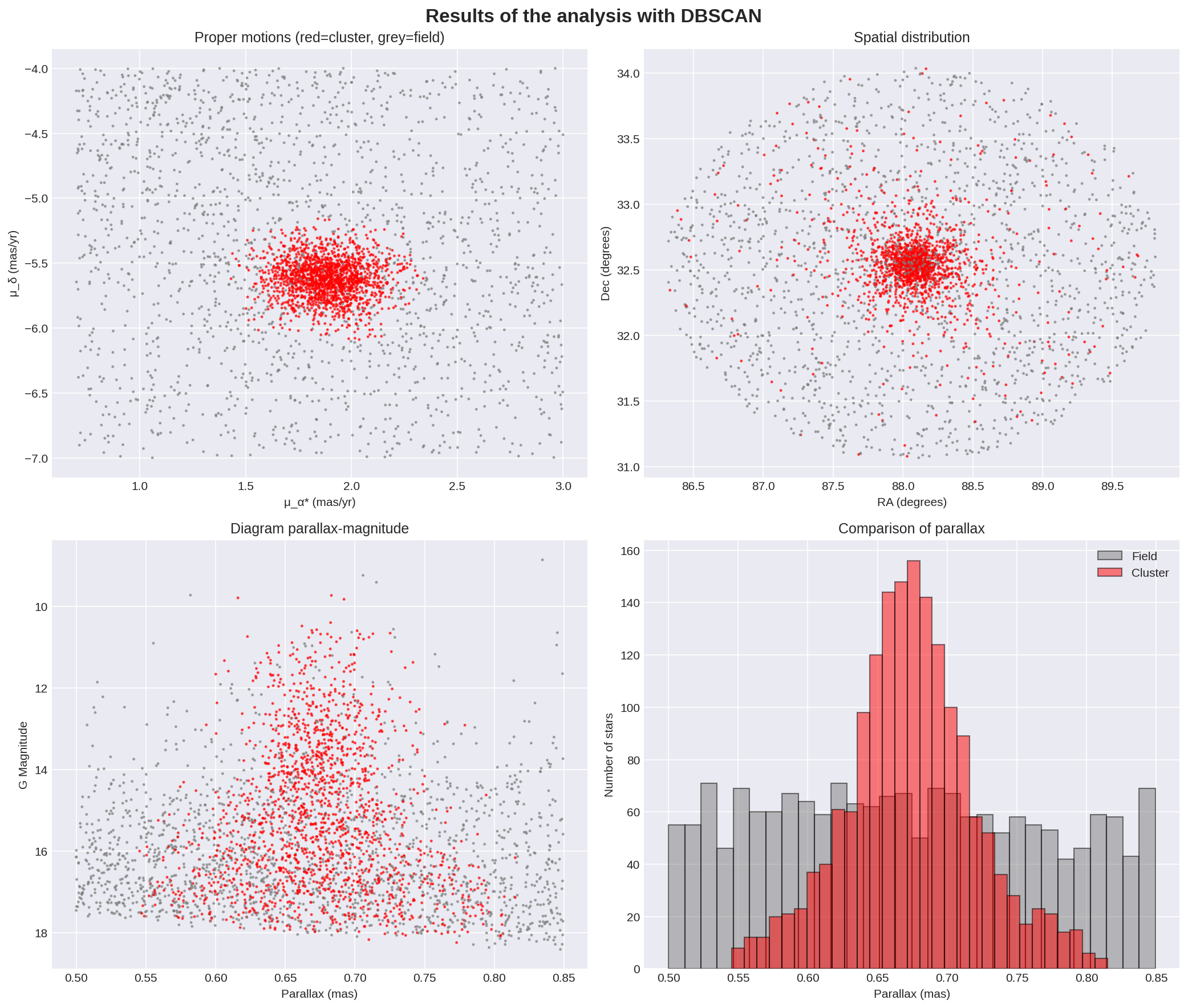

I will start with some graphs to see the results:

These four graphs allow us to verify whether the classification is consistent with current knowledge of the cluster or whether there is any data that would cause us to rethink the algorithm’s parameters.

1. Proper motion diagram

The proper motion diagram is perhaps the most important: the stars in the cluster were born together and travel together through space, so they will form a compact group in this diagram. The stellar field is composed of stars of different ages, distances, and galactic orbits, so it will appear scattered. The clear separation between these two groups is what makes membership analysis possible. The generated diagram clearly shows how DBSCAN correctly identified the core of the cluster without significant contamination in the kinematic space. The cluster in red is very compact, centred at (μ_α* ≈ 1.9, μ_δ ≈ -5.6). The field stars in grey are scattered throughout the space. There is no overlap between the two.

2. *Spatial distribution**

The distribution shown in the generated graph is consistent with what is expected: a central core centred at ≈(88.0°, 32.7°) and a radius of ≈0.3-0.4 degrees. No substructures or multiple cores are apparent.

3. Parallax-Magnitude Diagram

This diagram shows the relationship between the absolute magnitude of the members vs. distance (parallax). Since the stars in the cluster are at the same distance, we expect to see a vertical column centred at 0.67mas with es

4. *Parallax histogram**

This diagram shows the number of stars versus parallax. I would expect to see a Gaussian distribution centred at 0.67 mas, as the stars in the cluster should all be at approximately the same distance, with a higher concentration in the centre of the cluster. What we see is a central peak at ≈0.67mas, with a height of ≈155 stars/bin. The shape is Gaussian and the width at half height is ≈0.04mas (0.65-0.69 mas).

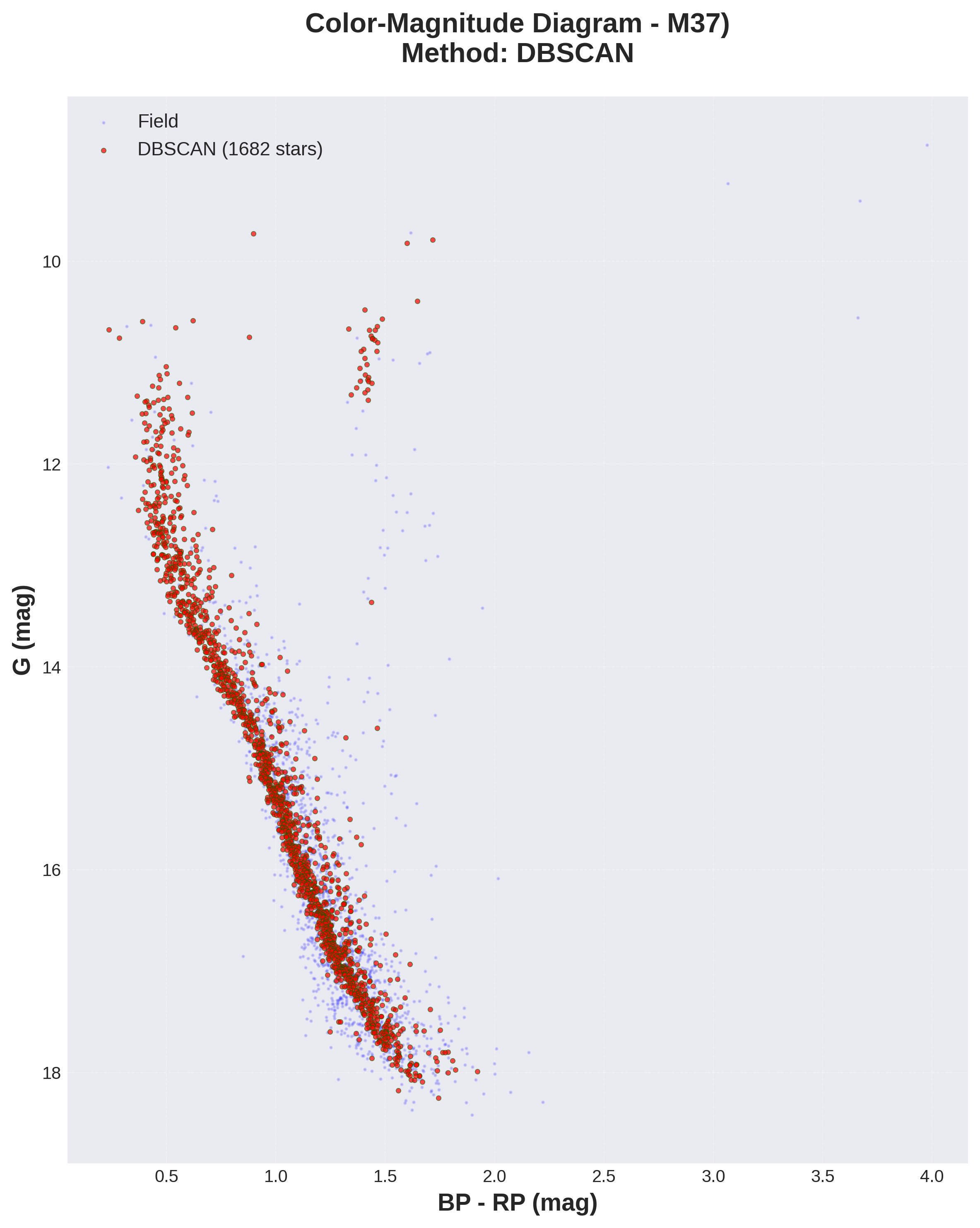

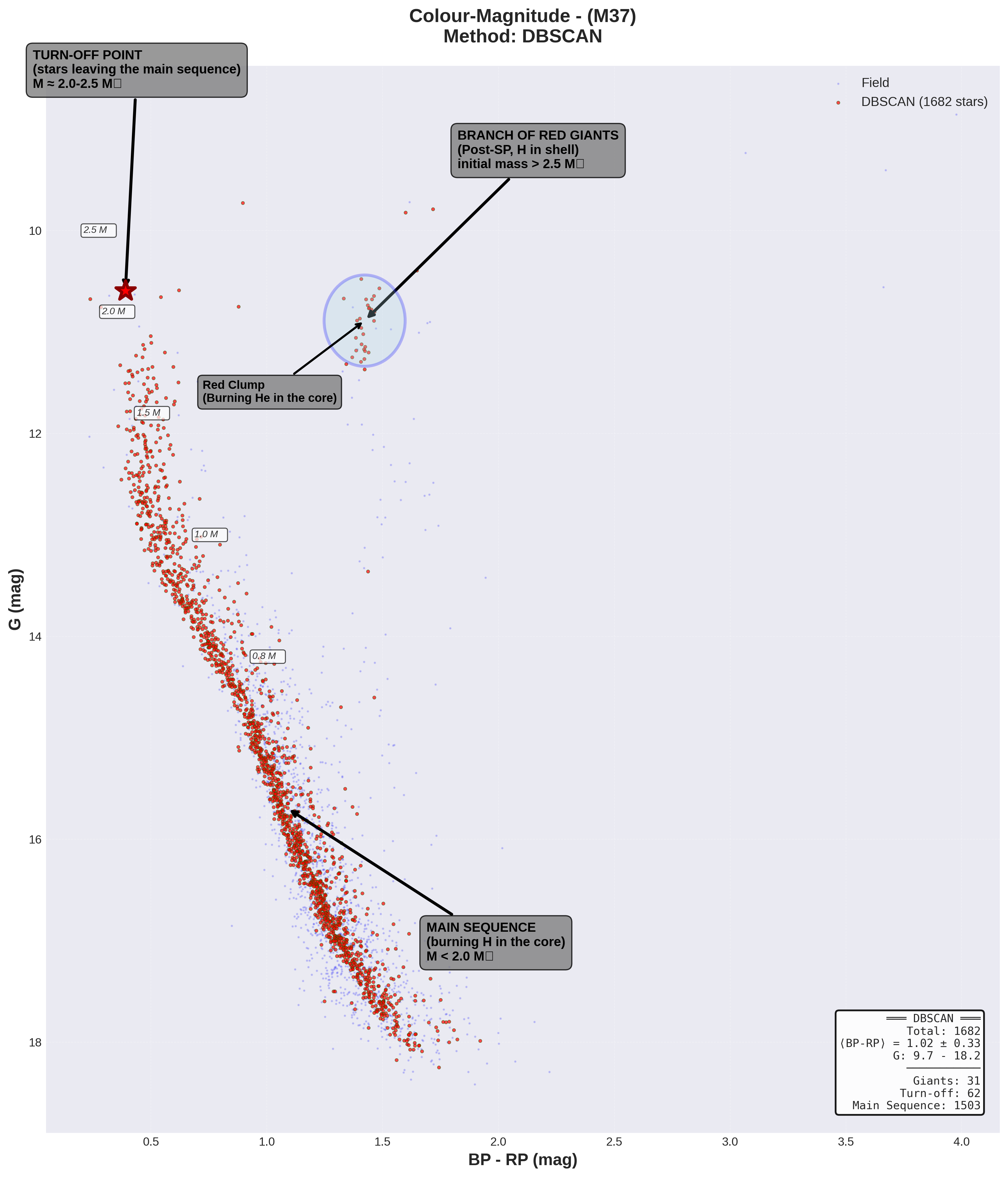

5. Colour Magnitude Diagram (CMD)

This diagram is key to the entire analysis: the colour magnitude diagram. In this diagram, we represent the stars identified as members of the cluster by showing their absolute magnitude (luminosity) against their spectral type. The luminosity, or absolute magnitude, is data that we obtain directly from Gaia’s phot_g_mean_mag field (absolute magnitude in the G band). On the x-axis of the diagram, we use bp-rp, obtained from Gaia’s phot_bp_mean_mag and phot_rp_mean_mag fields (absolute magnitudes in the rp and bp bands). A small BP-RP indicates that it is a blue, very hot star (≈10,000K), while a large BP-RP indicates that it is a blue, cool star (≈3,000K).

This diagram provides a wealth of information, which I will try to explain in several points:

5.1. Narrow and continuous main sequence The main sequence line appears correct, from BP-RP ≈ 0.5 and G ≈ 12 (corresponding to very massive, hot, blue stars) to BP-RP ≈ 2.0 and G ≈ 18 (low-mass, cool, red dwarfs). The trajectory does not show any jumps, and it is also very narrow (low dispersion). This low dispersion indicates that the identified stars are of the same age and metallicity. Why?

Here I will introduce several concepts. The position of a star in the CMD diagram basically depends on its mass. And the mass of the star determines its duration in the main sequence: more massive stars, due to greater gravitational pressure in the core, burn hydrogen at a faster rate than less massive stars. This duration is determined by the rate at which the fuel burns. The life of a star on the main sequence can be approximated with this formula: t = 10¹⁰ (M/M☉)⁻².⁵.

| Mass | Time in MS | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 25 M☉ | ~7 Myr | Very massive, very short life |

| 15 M☉ | ~11 Myr | Supergiant |

| 10 M☉ | ~20 Myr | Type O/B stars |

| 8 M☉ | ~35 Myr | Type B |

| 6 M☉ | ~65 Myr | Type B/A |

| 5 M☉ | ~95 Myr | Type A |

| 4 M☉ | ~180 Myr | Type A/F |

| 3.5 M☉ | ~270 Myr | Type F |

| 3 M☉ | ~400 Myr | Type F |

| 2.5 M☉ | ~630 Myr | Type F/G |

| 2.2 M☉ | ~850 Myr | Type G |

| 2.0 M☉ | ~1,100 Myr | Type G |

| 1.7 M☉ | ~1,700 Myr | Type G |

| 1.5 M☉ | ~2,400 Myr | Type G/K |

| 1.2 M☉ | ~4,900 Myr | Type K |

| 1.0 M☉ | ~10,000 Myr | Sun (Type G2V) |

| 0.9 M☉ | ~14,000 Myr | Type K |

| 0.8 M☉ | ~21,000 Myr | Type K |

| 0.7 M☉ | ~32,000 Myr | Type K/M |

| 0.5 M☉ | ~80,000 Myr | Type M |

| 0.3 M☉ | ~200,000 Myr | Dwarf M |

| 0.1 M☉ | >1,000,000 Myr | Late Dwarf M |

During this phase, the star remains in an almost fixed position in the CMD. When it exhausts its hydrogen, the star “moves” upwards and to the right in the diagram, towards the red giants.

If stars were not all born at the same time, we would see that in the range of massive stars (between 3 and 4 M☉) there would be some that had already left the main sequence and other younger ones that would still be in the main sequence: some would have already consumed their fuel, and others would still be in that phase. But we do not see that; in the upper left part of the diagram, all the stars have moved towards the red giant phase.

The similar metallicity of the stars identified as belonging to the cluster would also be explained by this low dispersion. When we talk about metallicity in stellar composition, we always refer to the presence of elements heavier than helium (Fe, C, O, etc.). Different metallicity has effects on opacity: the higher the metallicity, the greater the opacity and therefore the cooler the temperature. This implies that two stars of the same mass and age would be in the same vertical position but not horizontal: the one with higher metallicity would be redder. In the diagram, we would see great horizontal dispersion. It also has an effect on the rate at which material is consumed in the core, which would result in different luminosities.

The stars in the cluster formed from the same molecular cloud with the same chemical composition, and the chemical composition is virtually identical for all stars.

5.2. Visible turn-off

The turn-off is key information that can be extracted from the CMD diagram, as it will provide the age of the cluster. To understand why, let’s first look at the diagram. The diagonal main sequence is clear. There comes a point where it curves to the right, at BP-RP~0.4-0.5 and G~10.5-11 approximately. That is the turn-off point, and it can be objectively defined as the bluest (lowest BP-RP) and brightest (lowest G) point on the main sequence before it curves towards the giant branch.

The turn-off marks the point where stars are exhausting the hydrogen in their core and begin to evolve off the main sequence. Its position will tell us the luminosity, temperature and therefore mass of the stars that are in that phase. With the table above, we know how old those stars are, because we know the age at which they end their life on the main sequence.

To establish the age, we will have to compare the CMD diagram with isochrones from stellar models, curves from the CMD diagram for different ages of the cluster. There are several models based on isochrones (PARSEC, MIST, etc.), and in future posts I will investigate them and how to estimate the age of the cluster.

For now, what we do see is that there is a visible turn-off point in the diagram.

5.3. Clear red giant branch

In the CMD diagram, we also see the red giant branch in BP-RP between 1.5 and 1.8 and G between approximately 10-11. There will be about 30-35 stars in that range. These are stars that have already passed the turn-off point and are now evolving into red giants. They are cooler stars but still very bright. The fact that this branch is visible confirms that the cluster has reached an age sufficient for the most massive stars to have passed this point.

5.4. Field vs. Cluster Comparison

When comparing the stars in the cluster with the field stars in the diagram, there are also differences. The field stars are more scattered, and we see that there are less massive stars in the branch leading to the giants and that the dispersion in the main sequence is higher, suggesting multiple ages, metallicities, and distances.

Conclusion

In conclusion to the entire project, I can say that DBSCAN correctly identified the M37 cluster. This will be confirmed with analyses using the other two methods (HDBSCAN and GMM). Once the members have been confirmed, I will begin studies of the cluster’s age, initial mass function analysis, unresolved binaries, and metallicity determination.

Personally, this process contributed greatly to the project’s objectives. To interpret the results, I had to read scientific publications on membership analysis, academic literature on star formation and evolution, and review concepts such as luminosity, temperature, mass, nuclear fusion… It was really rewarding.

The next two entries will repeat this process with the other two methods, and finally, a comparative analysis of the three with studies already published on this same cluster.